|

"Cities are extraordinarily resilient

places, as we witnessed immediately after September 11th in New-York City, and adversity, far from undermining civic confidence,

can bring about a renewed and determined spirit of community and common endeavour."

HRH The Prince of Wales

"Tall

Buildings"

(Invensys Conference, London, 11th of December 2001)

Brooklyn Bridge at Night

(Photo by Stephan Edelbroich)

"In New York the rising spires of the skyscrapers of lower Manhattan were finally invaded by the flat slabs of the International

Style, of which Chase Manhattan Bank was the first. These instantly reduced the scale and quelled the wonderfully competitive

action of the earlier towers. The whole pyramidal grouping of spires began to die.

The tall but inert twin chunks

of the World Trade Center seemed to kill the whole thing off at last. So big and dead were they that all the dynamic interrelationships

of the earlier buildings came to seem lilliputian, inconsequential in scale."

Vincent Scully

"Architecture, the Natural and the Manmade"

(St. Martin's Press, New York, 1991)

Manhattan, New York, June 2000

(Photo by spaceimaging.com)

Some Thoughts on the Future of the World Trade Center Site

by Lucien Steil

Manhattan New York on September 12th, 2001

Collected by Space Imaging's Satellite Ikonos at 11:43 a.m E.D.T

(Photo by spaceimaging.com)

Destruction and Reconstruction

We know of extraordinary examples of reconstruction from

the history of city-building and architecture. For example: Warsaw after the Second World War; Lisbon admirably rebuilt by

the Marquis of Pombal after the tragic earthquake of 1755; Catania in Sicily reinvented as a Baroque masterpiece after the

devastating eruption of the Etna volcano at the end of the 18th century; Luxembourg rebuilt in five years by French architects

and Italian and Austrian masons after the heavy bombardment in the 16th century by the French troops of Louis XIV; Brussels

rebuilt after the terrible assault of the same French Army (which in its time excelled in the most advanced arts of destruction);

the Spanish cities brutally eradicated during the Spanish Civil War and wonderfully rebuilt afterwards; etc.

There exist innumerable examples of tragic destruction by natural causes, and more often by the ruthlessness and wickedness

of human fury, which have been followed by cultivated efforts of successful reconstruction.

300.jpg)

Calle de la Iglesia, Brunete, Spain (1946)

A New Town rebuilt on the Ruins of the Old Town destroyed during the

Civil War in 1937

Germany after the Second World War might be one of the few exceptions. Finding herself about 50% destroyed, Germany did begin

some timid traditional reconstruction but soon changed to the strategy of total replacement--an application of the principle

of "tabula rasa", erasing what was left--and this obsession increased in intensity with Germany's postwar economic

recovery.

Dresden in 1945 at the End of the Second World War

(Photo Sächsische Landes- und Universitätsbibliothek Dresden)

(copyright SLUB)

Rather than rebuilding the 50% of her devasted self, Germany ferociously demolished remaining buildings, ruins, and city fragments

in order to wipe out the memory and physical permanence of her highly cultivated architectural and urban heritage. All of

that was replaced by a modernist nondescriptness, a punishment that the Germans deliberately called upon themselves. Their

motivation and justification for this deed was mistaking the beauty and refinement of their architectural and urban culture

as the main factors responsible for the moral and political tragedy of fascism.

In recent years, new efforts of reconstruction have fortunately led many German cities to a reconciliation with their urban

and architectural history: projects in Berlin, Potsdam, Dresden, etc. propose to intelligently rebuild civic monuments and

historic neighbourhoods destroyed during the Second World War or in the Postwar reconstruction!

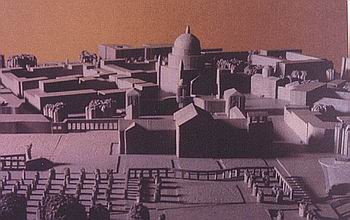

Project for the Reconstruction of Potsdam's Stadtschloss (1996)

The Prince of Wales' Urban Design Task Force

Generally, however it is not the cause of destruction that defines the typology of reconstruction. It is instead the paradigm

of the city lost, physically annihilated but intensily alive in the hearts and minds of its inhabitants--and continuously

present with its full potential as a collective historical memory--that influences reconstruction.

Reconstruction of Dresden (2001)

Project by Robert

Adam Architects

International Campaign for the Traditional

Reconstruction of the Neumarkt and Frauenkirche in Dresden, Germany

Visit the Dresden Page of INTBAU for detailed

information:

Reconstruction of Dresden

In the majority of historical cases, a new city has been built on the very foundations and ruins of the wounded or destroyed

city, according to an ideal, perfect image, which emulates the idea of the original more than any superficial resemblance.

The familiarity of this image was not due to a replicative fidelity, but rather to the truthfulness of city-building principles,

to the permanence of location and monuments, to the imitation of typological elements and of characteristic architectural

types and patterns rooted in the tradition of the place.

An Avenue in San Francisco (1986)

A City rebuilt

on the Ruins from the 1906 Earthquake and Fire Destruction

(Photo by Lucien Steil)

Quite often such new cities have been reinvented to become even more beautiful, more comfortable, and more memorable than

the one that had disappeared through the destructive violence of a natural event or human aggression.

When reconstruction has been conceived as an imitation of the destroyed city, the vividly acute memory it fostered was not

to become a paralyzing nostalgia fixed on a literal restitution. In the successful examples of reconstruction, there has

never been neither a design process that aims at a radical purification of memory, a reversal of memory into images and concepts

of salvation by a socio-cultural, architectural and urbanistic science-fiction. Such an alienation from the reality of a historical

urban and architectural culture is contrary to all aspirations of continuity and identity of its citizens, disdainful of their

desires of permanence and familiarity with their environment.

These considerations of continuity apply to the citizens of Manhattan, New York, who by brutal and tragic circumstances, find

themselves deprived of their cherished urban homeland.

World Trade Center Ruin, October 31st 2001

(Photo by A.P, Anonymous Photographer, New York)

Should we assume then that the site of the former WTC should be rebuilt in the image and in the spirit of its state before

the 11th of September 2001?

World Trade Center

(Photo by Stephan Edelbroich)

A view of what Nikos Salingaros and Michael Mehaffy have

criticized as "Geometrical Fundamentalism"

Skyscrapers and Memorials

Among the scenarios of reconstruction for the WTC site, besides the uninspired proposal of an identical replica of the former

WTC towers, the suggestion for pushing for even higher skyscrapers seems to be the most absurd and irresponsible. Leon Krier,

Nikos Salingaros and Jim Kunstler among other respected intellectuals, urbanists and architects have thouroughly demolished

the myth of the American skyscraper, and demonstrated its failures as a valid contemporary urban typology.

Nevertheless, against all reason and common sense, the question of building higher and higher continues to excite professional

hubris. The furious demand by architects for creative freedom (which includes dangerous experimentation) remains an unconditional

aspect of modernism. Those professionals have become the fiercest manipulators of the concept of a fictitious modernity, in

which the skyscraper is presented as an irreversible fact of contemporary civilization.

(Photo: Tripod Image Gallery)

"We shape our buildings, and afterwards

our buildings shape us."

Sir Winston Churchill

Instead of imagining or building places deserving a permanent record in the memory of our culture, architects declare upon

an authority which nobody has granted to them that the skyscraper is a sacred typology. (In our secular contemporary culture,

modernist architectural typologies --or typological aberrations according to Leon Krier-- are among the only concepts that

are held sacred, and are defended with religious fervor.)

New York, Historic Skyscrapers and New Skyscrapers

(Photo Tripod Image Gallery)

If the historic skyscrapers and some recent ones can legitimately be considered as remarkable contributions to the own architectural

and urban traditions of New York, there is no reason to regard skyscrapers as such as a sufficient and necessary condition

to the rebuilding of the WTC site.

Newer skyscrapers have no longer the contextual sensitivity and identifiable local

identity of earlier ones and look similar to any highrise structure in any place in the world. They contribute to destroy

the very tradition of a specific and sophisticated New York skyscraper type of exceptional height, of exceptional architectural

quality and of exceptional refinement in the New York skyline!

Manhattan with the Chrysler Building seen from Roosevelt Island

(Photo by Stephan Edelbroich)

The complexity and the integration of different scales in a dense urban setting characterize the urban and architectonic nature

of Manhattan more than the vertical acceleration of monolithic highrise structures. A tradition which is not referring to

the best, to the most cultivated, and to the most truthfully human in a historic culture, is not worthwhile following!

The Chrysler Building in New York:

A Tradition of Excellence rarely followed by those who

claim to refer

to a New Yorker Skyscraper Tradition!

(Photo by Stephan Edelbroich)

Now, this privilege without any ethical codes, as well as the demand for a total experimental freedom--the right to put thousands

of people in buildings whose behavior under normal and crisis conditions cannot be predicted--are beyond belief. Architects

who claim such rights are the least qualified to represent a civic and cultural responsibility. Nothing really qualifies them

to propose positive, realistic and popular visions for the reconstruction of the WTC site.

The ability to articulate a collective memory and to reinvent an authentic urban quarter in Manhattan have to be founded on

more solid traditions. In order to achieve a real emulation of the "spirit of the place", and in order to consecrate

the urban community and its legitimate aspirations, the confusions of an unchained and irresponsible modernism appear ridiculously

wasteful and useless. Even more disturbing, its futile celebrations of failure and desolation are an incomprehensible provocation.

In a recent essay entitled "What ever happened to Urbanism?" architect and urbanist Rem Koolhaas declares:

"The seeming failure of the urban offers

an exceptional opportunity, a pretext for Nietzschean frivolity...we have to take insane risks...The certainty of failure

has to be our laughing gas/oxygen; modernization our most potent drug. Since we are not responsible, we have to become irresponsible."

Koolhaas is correctly diagnosing the failure of modernist urbanism. But what he proposes is far worse: In order to have urbanism

we have to invent new failures. This urbanism is not about cities but about something we do not know yet. The only thing we

know is that it does not have any of the qualities and characteristics of cities, like boundaries, streets, blocks, plazas,

neighbourhoods, parks, etc...No responsibility, only some Nietzschean jubilation and power.

In today's society, it is only architects who can just shout their most contemptuous remarks in the face of a civilized audience

without serious consequences. It means that they have come to enjoy a foolish uselessness. But they also use this parasitic

inefficiency to usurp power in academic institutions and to promote an architectural show-business, creating a most powerful

establishment based upon intellectual confusion and mystification.

Nikos Salingaros is right when he claims a kind of Hippocratic contract from architects and urbanists!

Nassau Street, Financial District, New York

(Photo by Stephan Edelbroich)

"The essential value and virtue of a city is almost entirely defined in how successfully it is able to help people connect,

wether for formal or informal exchange. This crucial function is defined and expressed in the networks of city streets, squares,

parks and plazas, all of which require disciplined and well-articulated buildings to form and frame them."

HRH

The Prince of Wales

"Tall Buildings"

(Invensys Conference, London, 11th of December 2001)

Rebuilding the WTC site into a Memorial is antagonistic

to the very life, dynamics, and nature of New York City... Moreover, it is a concept that impedes any true reconstruction

which is capable of supporting the true potential of the site.

It seems more reasonable to commemorate the tragedy of September 11th by means of a series of architectural

elements which have the traditionally proven capacity for articulating, --in an efficient manner--, the city's collective

memory. The obsessive concept of a Memorial should not overthrow the equilibrium of the more essential issues of urban reconstruction.

It would be reasonable to have a commemorative chapel, a

square or park with a monument dedicated to the victims of the tragedy; maybe

a larger urban plaza integrating the splintered ruins of the WTC, and maybe--as have been often suggested--a sculptural figure

honouring the heroes of September 11th, in particular New York City's firemen. It would however be absurd to conceive a monumental

"Theme Park" dedicated to a sort of commemorative museography of the WTC tragedy.

The most important memorial is the city itself, the inhabitated

and thriving city, which continues to live and to celebrate life rather than despair and desolation. The most beautiful monument

on the WTC site would be the regeneration of an even more beautiful and comfortable city, transcending pain and sorrow through

the construction of a well-proportioned, familiar and harmonious urban architecture.

For it to succeed in its aims, its spirit will have

to be the opposite of the absurd challenges of an irrationally monumental, triumphal, and self-righteous architectural

and technological madness that we see going up elsewhere.

Neigbourhood in Manhattan: A Village in the City

(Photo by Lucien Steil)

Principles of Reconstruction

To urbanists who refer to an authentic culture of the city,

and who are sympathetic to the urbanist theories of the New Traditional City as defined by Leon Krier and Andres Duany, I

would like to ask: "Can you, on the basis of your professional integrity and civic sense, support and justify any skyscraper

whatsoever?"

If one accepts that in a walkable urban neighbourhood no

distance should exceed a 10 minutes walking distance, how then could one accept in one single building vertical distances

that are far beyond the physical potential of an average urban pedestrian? How could one reasonably accept the absolute

dependence upon mechanical systems of vertical transport in new buildings, while at the same time rejecting such a mechanical

dependence (as, for example: jitneys, moving sidewalks, or "people movers") on the surface of new urban neighbourhoods?

Two different souls in one heart?

Let's not forget that it took about an hour to walk the

stairs of the WTC, an athletic feat beyond many of its occupants' capacities. Even the time everyone had to spend in the elevators

and corridors to go from their office to the exit was far longer than the time required to walk comfortably through a traditional

neighbourhood!

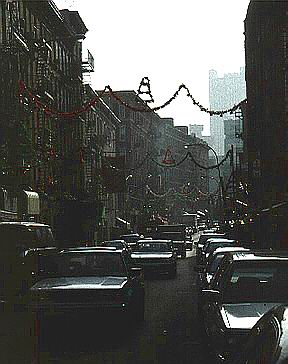

Little Italy, Manhattan

(Photo by Stephan Edelbroich)

New York is not only made of skyscrapers, but also of

many traditional neighbourhoods with buildings of normal height and traditional construction!

A true reconstruction has to return to an authentic genealogy

of Manhattan's historic urban construction. The powerful building typologies, either surviving or documented by a complex

history of architecture and urbanism, should be at the basis of an eventual planning effort. It is these rather than hollow

poetical speculations or conceptual experiments that ought to determine the future shape of the city. New York City possesses

a rich and extraordinary architectural memory, which cannot possibly be reduced to a history of skyscrapers.

Of course we all love New York's wonderful skyline,

gracefully shaped by beautiful architectural masterworks projected into the sky. Perhaps there will be other, future ones

adding to this fascinating "Crown City".

Exploring Manhattan's most popular, vital, and cherished

neighbourhoods reveals that an impressive part of the city is made up of buildings of normal height and of traditional construction.

Its villages and neighbourhoods like Greenwich Village, Soho, and Little Italy offer so many more excellent and time-tested

models for reconstruction than the few exceptional and splendid historical skyscrapers, or the more recent, faceless and boring

corporate highrises.

"Now it is true that there are some places

where towers and streets have worked successfully together, and one thinks immediately of the example of Manhattan, with its

uniform grid. Yet Manhattan is, and will remain, unique in sheer scale and wealth, and its towers are, of course, far from

the whole story of the city of New York. Jane Jacob's Greenwich Village with its tenements and brownstones, has been as much,

or more, a part of Manhattan's liveability as the Trump Tower and the Rockefeller Centre."

HRH The Prince of Wales

"Tall Buildings"

(Invensys Conference, London 11th of December

2001)

Greenwich Village, Gansevoort Street

(Photo by Stephan Edelbroich)

A truly dedicated reconstruction should imagine the WTC

site as an organic part of Manhattan, as an urban quarter dedicated to life and to its inhabitants. It has been scientifically

demonstrated that there is no functional necessity to group together and concentrate hundreds of firms, businesses, delegations,

representations, corporations, and offices in a single building. On the contrary, it has been confirmed that such concentrations

are confusing, disturbing, impractical, complicated, inefficient, unproductive, and are highly uncomfortable and destabilizing

to all the people forced to pass a major part of their days in those megastructures.

The organization of all the functions of the former World

Trade Center into a new urban neighbourhood of pedestrian scale with complex and mixed functions offers a less vulnerable

alternative than their original hyperconcentration. Above all, this is a far more authentic, efficient, and comfortable option

for reconstruction. Moreover, the creation of a complex, mixed-use, new traditional urban neighbourhood presents considerable

advantages for economic and socio-cultural regeneration, because the urban process can then be driven by more democratic and

pluralistic dynamics from the planning process through the building phases.

We have by now gotten used to New York's new skyline, and

despite everything, we still recognize the city's incredible fascination. Perhaps New York City has not only recovered from

the September 11th tragedy, but has also found a new social and cultural consciousness leading to a reinforced identity. I

would like to think that New York has above all rediscovered an acute awareness of the human being as the real scale of the

city.

The relationship of the urban community to its urban memory

and built environment remains profoundly hurt. Manhattan's wounds cannot be healed by the vain and foolhardy provocation of

a WTC replica, or by another overscaled highrise experiment....Those wounds will be healed only through the reconstruction

of an authentic urban quarter on the human scale. Rather than consecrating fear, power, forcefulness, and technological hubris,

or a reaction against terrorism, this time we have an opportunity to dedicate the reconstruction of Manhattan to life.

" The conclusion is, that for the service,

Security, Honour, and Ornament of the Public, we are exceedingly obliged to the Architect; to whom, in Time of Leisure, we

are indebted for Tranquility, in Time of Business for Assistance and Profit; and in both for Security and Dignity."

Leon Battista Alberti (1404-1472)

The photos of New York and other places by

Stephan Edelbroich can be viewed on the following website below:

www.photo-exhibits.com

An earlier version of this article was published in

Italian by ARCHIMAGAZINE in February 2002

ARCHIMAGAZINE

|